The archive I carry

The quiet rebellion of documenting life by hand: a love letter to journalling and the ancient soul of storytelling.

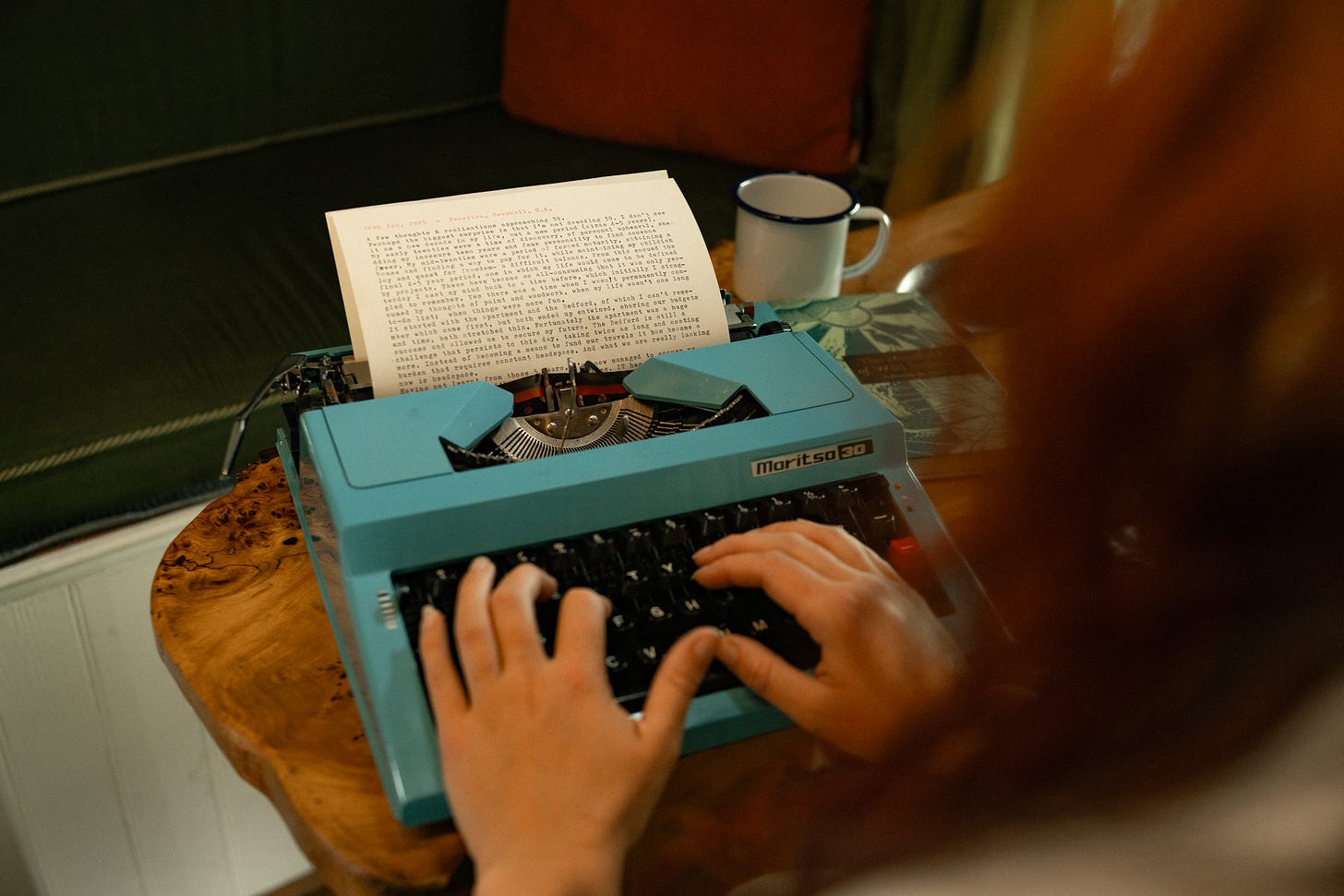

This morning I brewed a cup of tea, loaded a fresh page into my typewriter, and began to type. Letters grew into words which merged into sentences and swelled into paragraphs. Memories, thoughts and feelings all weaving together pieces of a vast story no one would ever read. This page would become one of thousands tucked away into my archive, the open-ended history books in the library of my life.

Most of us carry an archive of some kind— photos in an old biscuit tin, momentos on a pinboard, a digital trail on our phones, or simply moments etched in memory. The instinct to hold onto what matters— to say I was here, or this meant something— seems to live deep in us, like an echo passed down through time.

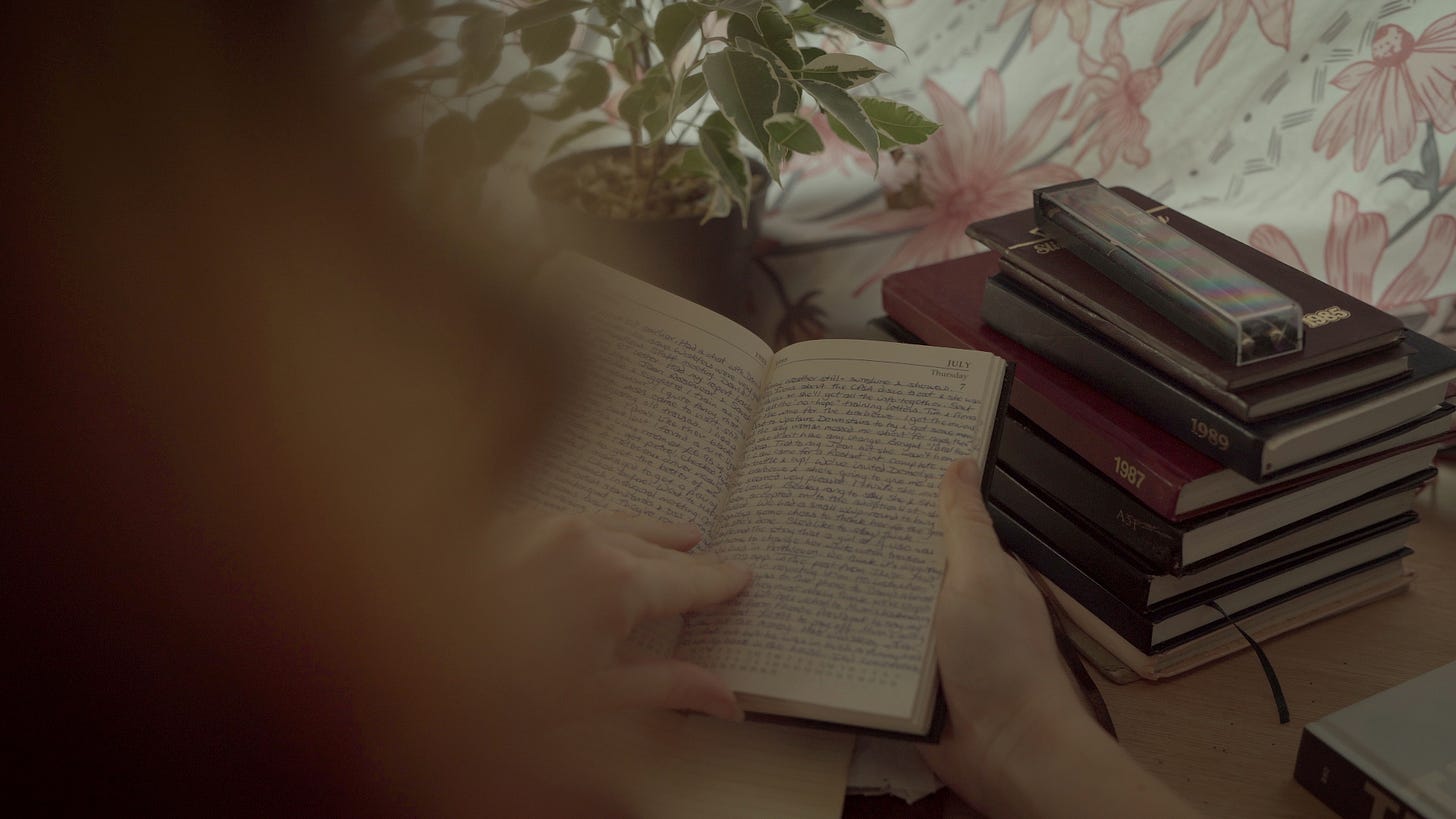

I’ve been keeping a diary since I was 7 years old. Just as my mum before me and my granny before her did. I still have all of my diaries; I still have all of theirs too. A book of hand-written poetry from 1967, a notebook of English literature from grammar school in 1970, a string of diaries stretching back to 1980. Most of them were started and never finished, as many of mine are.

Starting a diary at the beginning of a new year is easy, but continuing it through the year takes patience and persistence. Keeping a diary for over 20 years is a discipline in itself, which is why I’ve adapted my practice from writing a daily diary to a travel journal and now pages on a typewriter. To keep documenting my life in new creative mediums that match the eras of my life; I don’t want to lose a single moment to the sands of time.

Few things have grounded me more at the end of a day than writing my journal; whether that day was filled with unforgettable adventures, beautiful moments, anger or quiet sadness, it all gets preserved between the pages of my diary. It’s not just grounding— it’s healing. I’ve written my way through heartbreaks, losses, uncertainties. And while the problems didn’t vanish, something softened in the telling.

Sitting on our van’s doorstep, sun warming my face with a cup of steaming coffee beside me I scratch out the makings of a day in ink. Sure, I could type it all out on my phone, or my laptop– gosh knows it’d be quicker. But is it as personal as a tale scrawled in fountain pen, woven between Polaroid photos, pressed flowers and maps?

My journal is an amalgamation of me, and all the me’s from all the present moments of my lifetime. Sandwiched together inside a leather-bound cover between small personal artefacts of a life lived; ferry tickets, festival wristbands, foreign coins, a scrap of Soviet wallpaper, a hand-drawn map from a stranger. Tangible pieces of personal history, evidence of a life lived and remembered. Everyone I know has a box full of momentos they can’t bear to throw away; I think what we choose to keep says something about who we are, and speaks to our tendency for nostalgia.

Flicking through the brittle yellowed pages of my mother and grandmother’s diaries allows me to feel connected to them. Not in an abstract way, like looking at old photos, but in a visceral way: reading their thoughts, the nuances of their feelings and the little details that mattered on that day that would otherwise fade into time. It reminds me that spirit can linger not just in places, but in ink. That time may separate us, but story collapses the distance.

That’s exactly the significance I find in my own writing. It’s less a discipline, more of an instinct to capture, to document.

Someone asked me recently if I write my pieces from memory or keep a diary– “both,” I replied. “The memories are the building blocks; the diaries sketch in the finer details, things that would otherwise be lost.”

Even those who don’t keep journals still tell stories— to friends, to children, to themselves. Maybe we’re all archivists in our own way. I feel privileged to have so many records of my own life, and my family’s. Photos and stories of our house being built; birthdays, New Years and Christmases. The moment I was born– “At 6:02am Lucy Demelza was finally born at 5lbs 9oz. A tiny miracle after all that agony. Her dad was beside himself with joy. The midwife said she’d never seen a father so delighted.” Moments from before I was born too, that allow me to understand them not just as parents, but as people.

Every moment of my life too exists in ink on paper; adolescent angst, passing my driving test, my first night in our van. One of my earliest diaries documents the day I moved to France through the eyes of a 9 year old– “Arrived at the house and I rode my bike down the lane and gazed at our neighbours sheep & chickens. We now have a letterbox, but no toilet and we have to pee in a bucket. YUCK! We walked to the bakers & bought some eclairs, qouissons and French bread. When we returned we sat in the garden on the granny blanket and made daisy chains. Dad removed the wood from the lounge & cut it up, threaded the rope & made a swing on a tree. It. Is. LOVELY.”

Aside from the shelves full of diaries, I also have boxes of photographs– hundreds of them, some as recent as my childhood, others stretching back to the 1800’s, ancestors I no longer know or recognise. Somehow their photographs have survived over a century to end up beneath my bed.

To have such physical evidence of my lineage shows that documenting our lives isn’t just a habit, it’s a thread of connection through the generations. It’s a whispered I’m here into the vastness of the cosmos. A quiet affirmation that our lives— small and fleeting as they may seem— hold meaning. That something of us endures in what we leave behind; tangible proof that we passed through, loved, grieved, wondered.

Humans throughout the ages have felt the need to document their existence, from ancient tales of bravery and adventure spread by word of mouth or cave painting to a simple I was here daubed upon a wall (the oldest such graffiti dates back to Roman times and reads: Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here, October 3, 78 BC. I think about this often.)

What is it that stirs us so and compels us to chronicle our lives, in the hope that they are not swept away like grains of sand on the wind?

Is it to leave a legacy– to descendants, or in cases such as Anne Frank’s, to millions? To create a sense of continuity across unfathomable ages? Or perhaps it is simply to ground ourselves by meditating on the day’s events, untangling emotions, making sense of experiences and solidifying memories.

For me it’s about story-telling, preserving moments of my experiences that I can draw on later on in my writing– such as this piece you’re reading now. It’s about expressing my creativity, free of judgement, and making sense of the passage of time in a world that feels like it’s always moving too fast. And imagining maybe, one day, my granddaughter leafing through my own yellowed diaries.

I load another page into my typewriter, pour another cup of tea. Dappled amber light flickers across my wall; I take a moment to breathe before entering another flow. The typewriter has not yet become a time-worn practise for me, whereas keeping a journal had become a burden, awash with feelings of guilt every day I fell further behind. In a culture obsessed with productivity and perfection, the idea of writing for no one, without agenda, can feel alien. But I think that’s exactly what makes it sacred. Journalling demands presence in a world that rewards distraction.

My fingers punching each key, returning the carriage with a ding feels visceral, tactile. I thought that not being able to flicker them across a computer keyboard would be agonisingly slow; instead my thoughts trickle down into words that are stamped onto paper consciously, intentionally. There’s no backspace button; every smudge and spelling mistake is permanent, as are the pages I type. There’s no edit, no print, and somehow the process brings the stories to life, pulling them out of the invisible digital space and into the real world. It feels like a quiet analogue rebellion in a fast digital world where things vanish with a swipe or a scroll.

That’s why I’ve started printing my photos; to not just see them but hold them, feel them. To have something physical to add to my family archive, so it continues to grow— so that long after we’re gone, something of us still remains.

Thanks for reading; this piece was very intimate and deeply personal to write, and I hope it stirred something in you to read— a memory, a moment, a trace of your own archive. I’d love to hear your stories.

You can hit subscribe below if you’d like to receive more of my stories, reflections, and handwritten fragments from the road. No noise— just quiet words, straight to your inbox every so often.

–Lucy

Really enjoyed your thoughts Lucy. What a beautiful and gracious start to life you enjoyed and i definitely think we should change the spelling of croissants to yours! I probably only ate my first croissant when i was an adult but one child hood memory i have is of going out into town every once and a while with my maternal grandmother who lived with us and she would treat me to lunch : tomato soup, fish and chips and then a chocolate eclair!